Archive for the ‘Novellas’ Category

Catching Up pt. 3: A Natural History of the Senses, The Housemaid, North and South, The Book of the City of Ladies, Epileptic

In A Natural History of the Senses, Ackerman draws from a number of sources and memories in a meandering rumination about the senses through which we understand the world and interpret our own human experience. It is particularly hard to communicate the specificity of different physical sensations, but Ackerman writes about smells, touch, and the like so effectively that these mercurial interpretations manifest concretely and jump straight off the page, making the reading experience, well, sensual. The book is filled with interesting trivia, such as that smell was likely the first sense developed in the primordial oceans by the earliest living organisms, and I enjoyed the recounting she did of an interview with a professional “nose”, or perfume mixologist. Clearly I was most won over by the chapter on smell, as it sticks most strongly in my memory. However, I became increasingly annoyed with Ackerman and her frequent, bizarrely specific and lengthy descriptors. They often distracted from her main point and felt unfocused, a feeling intensified by the book’s format of short, thematically arranged but otherwise non-sequitor chapters. Also, while not generally opposed to heavy reliance on anecdote, hers felt obnoxiously self-referential and pompous. So, while the subject matter was fascinating, I didn’t really get along with Ackerman very well and will likely avoid her other writing.

One day, an older woman labeled a “witch” and disowned by her grown children finds a dead infant abandoned behind her hut in rural Ghana. Word spreads quickly through her village and suddenly everyone is arguing about who is to blame, with men vilifying the imagined neglectful mother and the women bemoaning the sad arrogance of undependable men. But as the true story of what happened is told through the perspectives of a number of women, it becomes clear that this child’s death is not the fault of one or another sex, but a society in which exploitation is quickly becoming a dominant means of attaining wealth. It begins when a young housemaid travels from her village to Accra to work for a wealthy older woman whose deceased husband’s family believes that her money rightfully belongs to them. The housemaid gets caught up in a plot of inheritance to win back the money for the husband’s family, but does not realize that her employer, though happy and confident in her independence, is not free of the sexual demands of the businessmen who remain in a class above her and so is not easy to manipulate. Nor does she understand that her own family’s motives may not be good for her, personally. The final telling of what happens to her baby is tragic but it is the fault of no individual: instead, it is the result of greed and an caustic individualism. A very worthy novella that counts toward Kinna’s Africa Challenge.

I’d been wanting to read North and South forever, but passed up the North and South read-a-long because it overlapped with my trip to Kenya and then promptly forgot about it. Even though I coincidentally ended up reading it at the same time as the read-a-long, I guess it’s still good that I wasn’t signed up because I didn’t have regular internet access nor the time to participate in the discussions, but anyway. I had huge expectations for this book, and while I enjoyed it, it fell just a little flat for me. It’s hard not to compare Gaskell to her contemporaries: not as much nuance as Austen, not as righteous as Dickens, less detailed than both. Perhaps such comparisons are unfair, but some combination of Austen and Dickens is what I thought I was going to get. Margaret, who moves from an idyllic country village to a busy, crowded industrial town, falls in love with the rugged Mr. Thornton (about whom I agree with Iris is a much more worthy love interest than most of Austen’s suitors ;)). There, she befriends some of the working poor that she’d previously been so judgmental about, and sides with them in a strike against factory-owner Thornton. Thornton, a proud, self-made man, learns through Margaret to sympathize with those less successful than he in “working their way up” while Margaret reconciles herself to the reality that the country isn’t exactly paradise for the poor, either. Culture clash, class, and the industrial boom frame this troubled love story, and I appreciate how direct Gaskell was in dealing with such themes. However, there was a bit too much compromise and neatness in the way it all wrapped up for my taste. Still liked it, though, so will try more of Gaskell.

This was (ahem) the FIRST book listed for The Year of Feminist Classics challenge* and yes, I only got to it last month. This book was written by Christine de Pizan, the only (?) professional female writer in late fourteenth century Europe. It is impressive not only that she was able to support her family with her writing at this time, but that she was able to do so while unequivocally challenging the most common anti-woman sentiments of her day. Here, she imagines a scenario in which Reason, Rectitude, and Justice come to her aid embodied as three strong and lovely women to help her construct a city of positive history and mythology in which she will collect and house all the world’s most virtuous ladies. They do so first by debunking myths such as that women are natural liars, that they lack conviction and are emotionally weak, that they are selfish and are intellectually inferior to men. Much as Mary Wollstonecraft would do almost four hundred years later in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, de Pizan argues that it is the way in which society brings girls up differently from boys that makes these stereotypes appear true and universal, but that given an equal education, girls would show as much aptitude as boys and in the same subjects (she does, however, fall very short of actually advocating for this). While her argumentation rested on reworking mythology, and this is not an acceptable form of debate nowadays, it was then–and since I was unfamiliar with so many of the stories, I kind of got a kick out of ’em despite the fact that it became very, very tedious reading. All the stuff about being a good, chaste wife etc. was irritating to my modern sensibilities, too, but I get that then she was reacting against the fact that women were only thought to be about their bodies, rooted in materiality with no spiritual or mental inner lives and value. I wouldn’t call this book relevant for feminists today, but I still enjoyed it as a feminist for the times when de Pizan utilized her stinging sense of humor and because it really made me consider context. It’s interesting to see that some ideas which are completely regressive and sexist now were once a step AWAY from an oppression that we still know, but in a completely different transformative phase. Of course, not all reactions against oppression are “progressive”, nor can that word be applied evenly across cultures and eras, which raises a lot of important questions about what constitutes progress in any given situation.

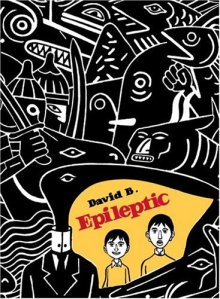

Epileptic is the deeply troubling autobiographical story by David B., formerly Pierre-Francois Beauchard, whose life has largely been shaped by his brother’s epilepsy and his family’s never-ending search for a cure. Epilepsy was little understood in 1960’s France when Jean-Christophe had his first seizure, and one of the most horrific aspects to this family history is how cruelly Jean-Christophe was treated by children and adults alike, alienating him, his siblings, and his parents from the community as punishment for exposing them to the symptoms of his illness. Their parents move Pierre-Francois, Jean-Christophe, and their sister in and out of various new-agey macrobiotic communes, inspiring hope in an unrelenting succession of mystical mentors and spiritual healers who are ultimately as lost as they are. While his parents experience increasing guilt after every failure to “fix” their eldest son and his sister becomes despondent with depression, David B. pours himself into his illustrations, picturing epic uphill battles that signify his struggle against his brother’s sickness. His thick, bold-lined drawings are appropriately claustrophobic and disconcerting, adding a fantastical element to this tragedy. David B. is always honest, refusing to leave out the ugliest bits of his history and the resentment he sometimes felt toward his brother, whose disease he could never measure up to. Dark and moving; beautiful work and intensely raw.

*I think it’s time I admitted to myself and everyone else that I’m not going to catch up on The Feminists Classics challenge this fall like I wanted to. In fact, there’s only a few books from this year’s selection that I haven’t read, but even excluding re-reads, it just isn’t going to happen. Truth be told, I’ve been dealing with the aftermath of a Very Bad Thing that happened earlier this month in the life of myself and my friends and have had difficulty concentrating on books, so I know that if I don’t allow myself to read at whim I won’t be doing much reading at all, and I don’t want that. Sincerest apologies for committing to it and then only reading one book and not participating in any of the conversations**…hopefully I will get to all the others at a later date, as they all remain interesting to me. I still plan to host the last read when the time comes, but all reading projects and such will otherwise be put on hold or ignored.

**Hello, guilt.

The Death of Ivan Ilych, by Leo Tolstoy

While I was completely bowled over by Anna Karenina when I read it a few years ago, I was pleased to be able to visit Tolstoy again without having to make such a long-term commitment to him. I will get to War and Peace eventually, but for now I crave nothing more than this short tale was able to provide.

Ivan Ilyich is an ordinary man with average ambitions and realistic expectations who aspires only to live pleasurably and with propriety. As a respected judge, husband, and father, he does his duty and does it well. He bows graciously to the authority of his superiors and enjoys the position of power he maintains in respect to others. He is pleased with himself and with his achievements, until he falls ill as an older man.

Just as there is nothing remarkable about Ivan Ilyich’s life, there is nothing remarkable about his slow struggle toward death. His physical and spiritual decay is monstrous only because it is so banal. Ivan Ilyich considers himself perfectly satisfied in health, but in sickness he questions all the big life choices that have led to the present moment of his dying. He is angry and resentful that he must be a burden to his family, and that, like him, they are unable to fully understand what is happening to him. He sees nothing special in life, yet cannot surrender to leaving it. His last hours are spent producing a terrible scream, an insufferable howling “O” sound that haunts his family for an entirety of three days.

There is nothing interesting about this story, which is what makes it so stunning. An ordinary death is a predictable end to an ordinary life, and yet that ordinariness is itself what is so frightening. What the accused are to the judge, we all eventually become to death (ahem, are you totally bummed out yet?). This is an important reminder for all who can to live extraordinarily; for Ivan Ilyich’s battle is not only against death, but the ways in which it both cloaks and exposes mediocrity in life.

This is an unsettling and articulate investigation of mortality which I’m sure only becomes more disturbing and poignant with time. Recommended, then, with the caveat that this is Heavy Stuff.

Schoolgirl, by Osamu Dazai

This book was kindly sent to me by One Peace Books, who have recently issued a new translation of the original work published in 1939.

The schoolgirl at the center of Dazai’s stream-of-consciousness novella is cynical, inquisitive, self-conscious, and superior all at once. She is a teenager, after all. Her mood swings are not just the ol’ adolescent hormones rearing their familiar, monstrous heads, though. As she takes us through a single day of her life, we see that she is battling demons both inside herself and out. Her classmates may irritate her, but that is nothing compared to the turmoil she feels at the recent loss of her father and the heavy cloud of mourning that weighs upon her mother. Her immediate concerns about teachers, friends, and house-guests seem unimportant on their own, but taken together they mark a process by which our troubled narrator learns to construct her own identity in what she sees as a world of cowardly conformity. She is quick-witted and a reader herself, wholly caught up in books and stories which, of course, I found wonderfully endearing.

The unnamed schoolgirl is eager to grow up, to be treated like an adult. At the same time, though, she dreads becoming a woman. She sees the lack of personality in her friend Kinko as inextricably linked to her incredible femininity and, upon recalling a heavily made-up woman she saw on the train that morning, proclaims that “women are disgusting” and “impure” (p. 47).

It’s as if that unbearable raw stench that clings to you after playing with goldfish has spread all over your body, and you wash and wash but you can’t get rid of it. Day by day, it’s like this, until you realize that the she-odor has begun to emanate from your own body as well. I wish I could die like this, as a girl. (p. 47)

I take these comments to be expressions of the physical and psychological disturbance she feels at the changes occurring both within her own body and in the social role she’s expected to play as a Japanese woman. She seems unimpressed with the examples of both her female teacher and her mother and dreads being confined to a similar fate. I do hope that my reading of her repulsion as masking disdain for sexist constraints imposed upon women, rather than actually being a set criticism of women as people, is not too generous! Though this is a big generalization, I do think that a lot of young women struggle with this kind of internalized misogyny and experience it as a very personal defect, which would support my interpretation. Whether it was Dazai’s intent to invoke this internal process, though, I am not certain.

The book’s strength lies in Dazai’s ability to write a story that is both culturally specific and widely relatable. Its about navigating Japanese society and cultural norms as a girl, but it’s also simply about being youthful, restless, and discontent. Some of the schoolgirl’s voice was obscured by the roller-coaster of emotions evoked throughout the text, but perhaps that’s part of the point. Ultimately, I think that enjoyment of Schoolgirl might hinge on one’s desire to revisit (or just visit, if you are a younger reader) both the idealistic highs and despairing lows of adolescence. At this point, as someone who is no longer a teenager but still far from getting all nostalgic about it, I am pretty ambivalent about doing that and so my feeling about the book was a bit ambivalent as well. It’s ironic that this ambivalence is due to Dazai’s success in writing about such a particular emotional and developmental state. While I am short of enthusiastic about Schoolgirl, it was a good introduction to Osamu Dazai, who I am now interested in reading more of. Not a favorite, then, but well worth the read.

Catching Up, Part 3

I’m back! Here’s what I read while I was out of town:

Beginning with a wedding and ending with a funeral, The Group follows the lives of eight women who graduate from Vassar in 1933 through the next ten years of their lives. These privileged women strongly identify themselves as part of a set based on their shared school experience and their educational status, which reads as a bit outdated. However, their experiences with, and conversations about sexuality, birth control, family problems, and workplace discrimination kept the book relevant and engaging. It was this, and a focus on long-lasting but malleable friendships, which drew me in. McCarthy writes in a meandering way and moves so easily from one character to another that the shift between them is almost imperceptible, and that didn’t hurt either. Her style reminded me a bit of Virginia Woolf’s in Mrs. Dalloway which–of course–is a high compliment.

Full disclosure: I know Miriam Sagan personally, and thank her very much for sending me a copy of this book. I don’t plan to let that sway my “review” at all, but thought it right to mention it. I don’t read a lot of poetry–I should read more though, because often when I do I end up enjoying it more than expected. This collection brings together the poetry of three friends sharing their experiences of love and loss, some of which overlap, and all of which are fairly accessible to non (or rare) poetry types like me. The natural overlap of experience is perhaps the most interesting outcome of this project since it allows for a plurality of perspectives toward singular events. My favorite part, though, was the evocative imagery of my first home, the Southwest, which is a near-constant setting for these poems. I also liked how, through their poetry, you could feel the real-life bonds that exist between the authors and see how the major events of their individual lives have informed their friendships. I hadn’t realized it before, but this book shares much of what I enjoyed most about The Group! A cathartic read.

In 1939, the French ship La Amistad sailed from Havana toward Puerto Principe, Cuba, with 56 African slaves on board. The slaves freed themselves from their restraints, mutinied, and were captured off the coast of Long Island. Questions about rightful ownership of both the ship and the people onboard fed a long-winded Supreme Court case, the resolution of which had a crucial impact on both international politics and the institution of slavery in the United States. For many New Englanders, this was their first interaction with Africans unmediated by the institution of slavery. It took them lengthy investigations and more than one translator to determine exactly where in Africa they had come from, and to hear their telling of the events aboard the Amistad, but immediately they were of widespread interest; people would come from afar to gawk at them in prison, where they were held until their freedom was finally granted in 1841, and abolitionists were quick to adopt their case. These events were widely publicized at the time, and are still quite fascinating. Unfortunately, this book was pretty boring. It’s brevity is one of the few things it has going for it. Intriguing history, but mediocre book. Too bad.

Set in early nineteenth century Andalucia, this short novel is a warning against the corruption of authority represented by the corregidor (insufficiently translated as administrator, or mayor) and symbolized by his three-cornered hat. This figure takes an interest in the local beauty, Frasquita, who is married to the miller don Eugenio. Frasquita and her husband decide to play a prank on the corregidor, but when don Eugenio begins to suspect his wife of running too far with the joke and succumbing to the corregidor’s sexual advances, he tries to one-up them by impersonating el corregidor and bedding his wife. The persistent idea that political corruption/and or gain, or “manliness”, or whatever, comes at the expense of women “belonging” to other men is annoying to me, and totally at play here. But I couldn’t help enjoying the humorous aspects of the story, which were many. And in the end, though each wife is fooled by the silly behavior of their husbands, they are not made fools of in the way their husbands are. In fact, they gain the benefit of each other’s friendship–so I guess that evens things out. This tale would not be out of place as one of those stories within a story that happen in Don Quixote, and so I liked it.

Bless Me, Ultima tells the story of Antonio Marez, a young boy from Guadelupe, New Mexico, whose life is forever altered when the curandera (healer) Ultima comes to live with his family during the second world war. He feels pulled toward two conflicting futures; one in which he honors his mother and her side of his family by becoming a priest and a settled farmer, and one in which he follows the wild, nomadic footsteps of his father’s restless dreams. He also struggles to reconcile his religious beliefs with the injustice he sees around him, and his existential struggles are made much more difficult when Ultima is accused of witchcraft by others in his community and people around him start dying. Though he learns wonderful things from Ultima, in the end only he can unlock the secrets to his destiny and forge his own spiritual path. Anaya is a masterful storyteller. This book was required reading for me in middle school, clouded by fond but vague, disjointed memory. It more than stood the test of time and was only improved by a second, more seasoned reading, and highly recommend it. I’ve just found out that Bless Me, Ultima is acutally part of a trilogy, and can’t wait to track down the other two books in the series.

And that’s that! Finally, I can get back to writing about books immediately (er, or at least shortly) after completing them. Welcome to summer, everyone.

So Long a Letter, by Mariama Ba

So Long a Letter was the second January pick for the Year of Feminist Classics Project, and at just 95 pages of lovely prose, it was one I was very grateful for following my struggle with Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft.

But don’t let that fool you: there is a lot of complicated material, emotion, and power to tease out of this slim novella.

Following the death of her husband, Ramatoulaye writes a letter to her friend Aissitou in which she tells her all about her husband’s decision years earlier to take a younger, second wife and her difficult decision, as a mother of twelve, to endure the imposition rather than break up her family. She is left with nothing of her own, and what happens to her is largely out of her control. Aissatou’s life has also been disrupted by her husband’s decision to take another wife but has, in contrast to Ramatoulaye, left her husband and taken her children to the U.S. where she has done very well on her own. Ba compares the two women’s experiences skillfully, so that neither seems “right” or “wrong” for reacting the way they have, which is one of the book’s major strengths. Through the meanderings of Ramatoulaye’s letter, Ba also expands her scope to encompass Senegalese politics and culture more broadly so that the reader is presented with a clearer picture of some of the reasons for, and results of, a system which leaves women vulnerable to this kind of expendability.

But, whereas the book tackles the unfortunate disadvantages for women within polygamist society, it is not without hope. What was most interesting to me was the contrast between what Ramatoulaye and Aissatou seemed to experience as an age-old problem with the excitement of Senegalese independence from France (1960) and what they imagine that does, or should, mean for women. Though women are sadly underrepresented in Senegal’s new government, they are not unaware of the momentous gains of women’s movements around the world. Of course, though Ramatoulaye desperately wants progress, the effects of modernization leave society “shaken to its very foundations, torn between the attraction of imported vices and the fierce resistance of old virtues” (p. 76). When she sees these effects take root in her own children, she finds that “progress” can be complicated to define, and more difficult to embrace than she had previously imagined.

I really was impressed with Ba’s ability to say so much with so few words. For example, the short bit about Ramatoulaye’s ventures to the movies by herself, and her hesitancy–then courage–in the face of disapproving or confused looks, says worlds, I think, about the everyday challenges she faces as a discarded wife (um, for lack of a better phrase?) while also reflecting her strength and development as a character.

As I’m sure is clear, I quite enjoyed this book and think it made a really great contribution to the Year of Feminist Classics project. I look forward to jumping into February’s read, The Subjection of Women by John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor (though you probably won’t see her credited many places for her contribution, Grr!) Feel free to join us at any time, for as long as you’d like, if you haven’t already 🙂

Houseboy, by Ferdinand Oyono

Toundi is a Cameroonian boy who is fascinated by his French colonizers. He escapes his abusive father by becoming houseboy to the head of the Mission, but when Father Gilbert is killed in a motorcycle accident, he goes to work for the local Commandant. He finds the Commandant, his wife, and the rest of his European masters alternatively intriguing and ridiculous. But through quiet observation he gets to know them well–too well for his own safety.

This is a short book, only 122 pages, but it packs a punch. It’s a critical look at colonialism, racism, and sexual politics through the eyes of a genuine and sympathetic narrator. Of particular interest to me is the way that colonialism forever changes and confuses Toundi’s perception of his own identity and that of his country and culture too, as in the end he asks “Brother, what are we? What are we blackmen who are called French?”

This may be a slim novella, but it’s weighty in substance and rich in thought. Recommended!